How the Web Works

Abbreviations

*[API]: Application Programming Interface

*[DNS]: Domain Name Service

*[ftp]: File Transfer Protocol

*[html]: Hypertext Markup Language

*[http]: Hypertext Transfer Protocol

*[https]: Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure

*[IP]: Internet Protocol

*[URL]: Universal Resource Locator

Introduction

If you want to be a web developer, you've got to know how the web works. Luckily, the internet was designed by incredibly smart people with accessibility in mind.

In this subunit, we'll teach you all the fundamentals of how the internet works: what happens behind the scenes when you type in a URL, how data passes between computers, what IP addresses are and how they work, the Domain Name Server, and much, much more. You've been using all of these services for years!

Goals

High level: what happens when you visit a URL in browser

Explain what IP and DNS are

Describe the different parts of a URL

Describe the request / response cycle

Compare GET vs POST requests

What happens when...

When I type http://site.com/some/page.html into a browser, what really happens?

This is a common interview question for software engineers.

How the Web Works

The internet is complicated. Really, really complicated. Fortunately, to be a software developer, you only need to know a bit. For people who want to work in "development operations," or as a system administrator, it's typical to have to learn more about the details here.

Networks

A network is a set of computers that can intercommunicate. The internet is just a really, huge network. The internet is made up of smaller, "local" networks.

Hostnames

We often talk to servers by "hostname" — site.com or computer-a.site.com. That's just a nickname for the server, though — and the same server can have many hostnames.

IP Addresses

On networks, computers have an "IP Address" — a unique address to find that computer on the network. IP addresses look like 123.77.32.121, four numbers (0–255) connected by dots. There are a lot of advanced edges here that make this more complicated, but most of these details aren't important for software engineers:

there is another whole way to specify networks, "IPv6," that use a different numbering scheme.

some computers can have multiple IP addresses they can be reached by

under some circumstances, multiple computers can share an IP address and have this be handled by a special kind of router. If you're interested in system administration details, you can learn about this by reading about "Network Address Translation."

127.0.0.1

127.0.0.1 is special—it's "this computer that you're on." In addition to their IP address on the network, all computers can reach themselves at this address. The name **localhost ** always maps to 127.0.0.1.

URLs

http://site.com/some/page.html?x=7

turn into:

Protocol | Hostname | Port | Resource | Query |

|---|---|---|---|---|

http | site.com | 80 | /some/page.html | ?x=1 |

Protocols

Protocol | Hostname | Port | Resource | Query |

|---|---|---|---|---|

http | site.com | 80 | /some/page.html | ?x=1 |

"Protocols" are the conventions and ways of one thing talking to another.

http—Hypertext Transfer Protocol (standard web) (How browsers and servers communicate)

https—HTTP Secure (How browsers and servers communicate with encryption)

ftp-File transfer protocol (An older protocol for sending files over internet)

There are many others, but these are the common ones. In this lecture, we'll focus only on HTTP

Hostname

Protocol | Hostname | Port | Resource | Query |

|---|---|---|---|---|

http | site.com | 80 | /some/page.html | ?x=1 |

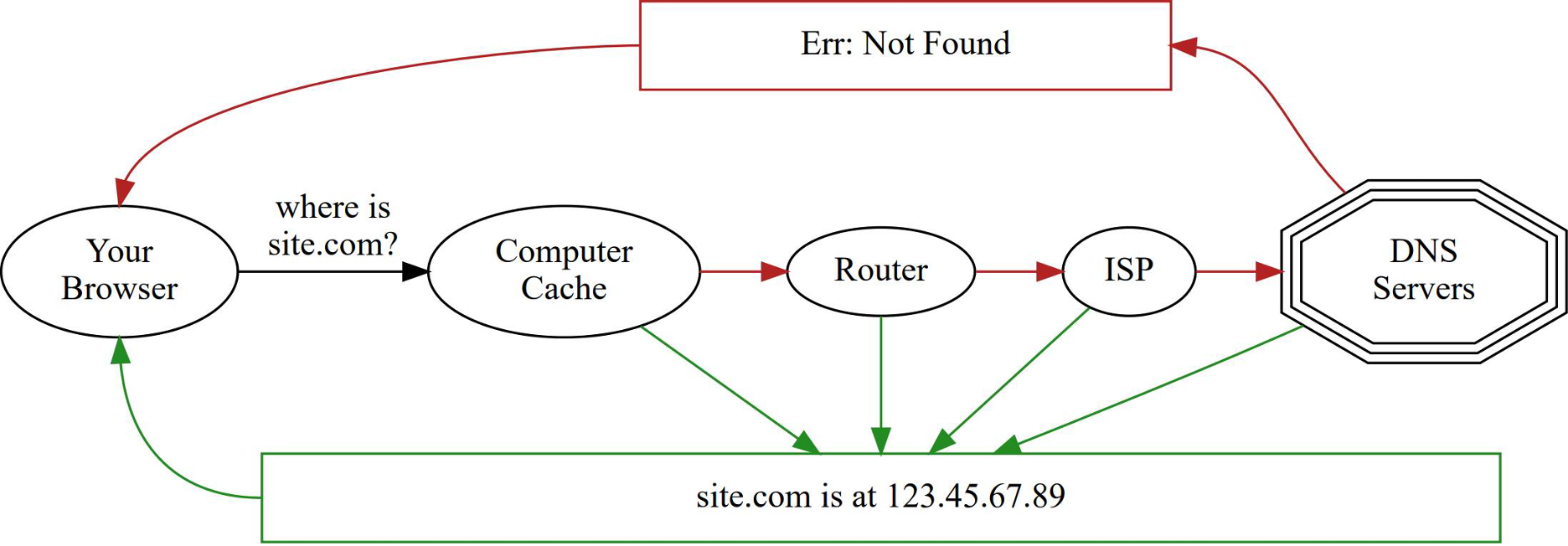

DNS (domain name service) turns this into an IP address

So site.com might resolve to 123.45.67.89

Port

Protocol | Hostname | Port | Resource | Query |

|---|---|---|---|---|

http | site.com | 80 | /some/page.html | ?x=1 |

Every server has 65,535 unique "ports" you can talk to

Services tend to have a default port

For HTTP, is port 80

For HTTPS, is port 443

You don't have to specify in URL unless you want a different port

To do: http://site.com:12345/some/page.html

Resource

Protocol | Hostname | Port | Resource | Query |

|---|---|---|---|---|

http | site.com | 80 | /some/page.html | ?x=1 |

This always talks to some "web server" program on the server

For some servers, may have them read an actual file on disk: /some/page.html

For many servers, "dynamically generates" a page

Query String

Protocol | Hostname | Port | Resource | Query |

|---|---|---|---|---|

http | site.com | 80 | /some/page.html | ?x=1 |

This provides "extra information" — search terms, info from forms, etc

The server is provided this info; might use to change page

Sometimes, JavaScript will use this information in addition/instead

Multiple arguments are separated by &:

?x=i&y=2Argument can be given several times:

?x=i&x=2

So

http://site.com/some/page.html?x=7

means

Turn "site.com" into

123.45.67.89Connect to

123.45.67.89On port 80 (default)

Using HTTP protocol

Ask for /some/page.html

Pass along query string: x=1

DNS

I want to talk to site.com

Unix (and OSX and Linux) systems ship with a utility, dig, which will translate a hostname into an IP address for you, and provide debugging information about the process by which it answered this.

Browsers and Servers

Request and Response

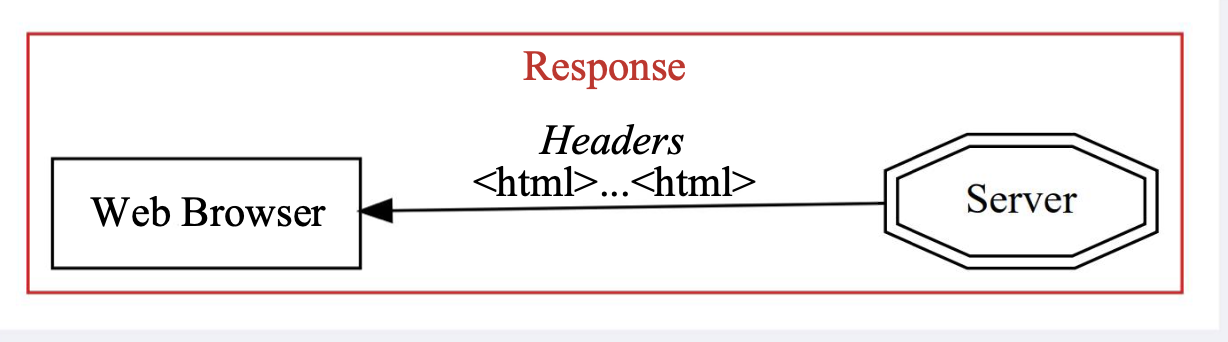

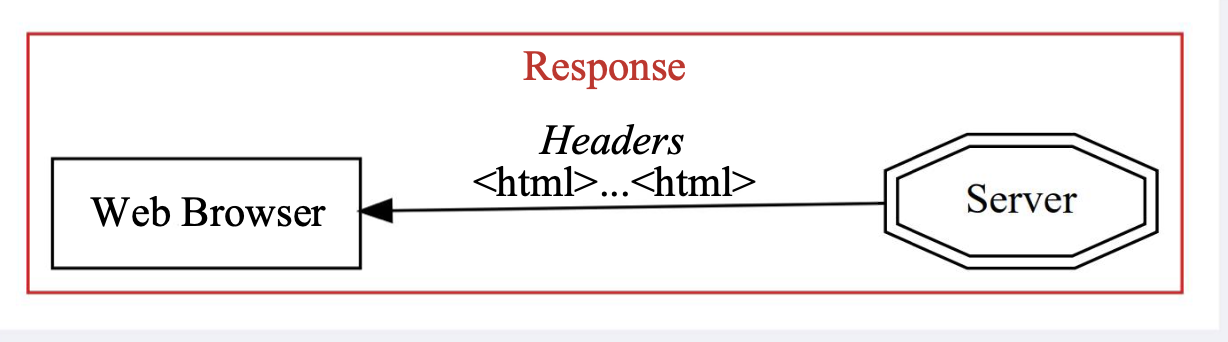

When you point your browser to a webpage on a server, your browser makes a request to that server. This is almost always a GET request, and it contains the exact URL you want.

The server then responds with the exact HTML for that page:

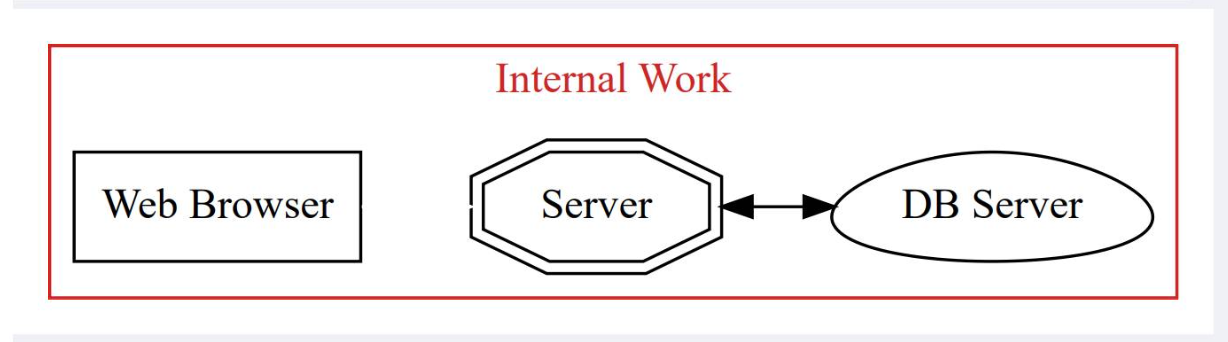

It's often the case, though, that the web server itself will have to do some work to get the page you want, often interacting with other things, such as database servers.

And then it can give back the response you want:

What's in a Request

Method (ex: GET)

HTTP protocol version (almost always 1.1)

Resource URL you want

Headers

Hostname you're asking about

Date your browser thinks it is

Language your browser wants information in

Any cookies that server has sent

And more!

What's in a Response

HTTP protocol version (almost always 1.1)

Response Status Code (200,404, etc)

Headers

Content Type (typically text/html for web pages)

Date/time the server thinks it is

Any cookie server wants to set

Any caching information

And more!

Watch a Request/Response

Response Codes

200-OK

301-What you requested is elsewhere

404—Not Found

500—Server has an internal problem

Serving Over HTTP

Just opening an HTML file in browser uses file protocol, not http Some things don’t work the same (esp security-related stuff) It’s often useful to start a simple HTTP server for testing

You can start a simple, local HTTP server with Python:

Server files in current directory (& below):

Multiple Requests

Sample HTML

demo/demo.html

CSS

demo/demo.html

Connects to site.com on port 80 and requests:

Response:

Image

demo/demo.html

Connects to tinyurl.com() on port 80 and requests:

JavaScript

Connects to site.com on port 80 and requests:

Hey, That's a Lot of Work!

Yes, it is

Requesting one webpage often involves many requests!

Browsers issue these requests asynchronously

They'll assemble the final result as requests come back

You can view this in browser console --> Network

Trying on Command Line

Curl (OSX)

OSX systems come with a utility, curl, which will make an HTTP request on the command line.

Hey...

Everything is a string!

Methods GET and POST

GET vs POST

GET: requests without side effects (i.e., don't change server data)

Typically, arguments are passed along in query string

if you know the arguments, you can change the URL

Entering-URL-in-browser, clicking links, and some form submissions

POST: requests with side effects (i.e., change data on server)

Typically, arguments sent as body of the request (not in query string)

Some form submissions (but never entering-URL-in-browser of links)

Always do this if there's a side effect: sending mail, charge credit card, etc

"Are you sure want to resubmit?"

Sample GET Requests

Sample POST Request

POST requests are always form submissions:

HTTP Methods

GET and POST are "HTTP methods" (also called "HTTP verbs")

They're the most common, by far, but there are others